Let’s take some of the complexity out of school improvement

Let’s take some of the complexity out of school improvement

It’s time that policy makers and some parts of the media took the time to understand the drivers of school performance.

Organisational structures continue to remain a focus - the latest example is grammar schools, but we have had countless other attempts over the years to pretend that structure is what drives improvement.

Yes, there are outstanding local authority maintained schools, grammar schools, faith schools, academies and multi-academy trusts. Go looking and you can find them. We could also find failing versions of all these types as well.

There is no doubt school improvement is a hard and complex job, but we do have a habit of making it harder and more complicated than it needs to be.

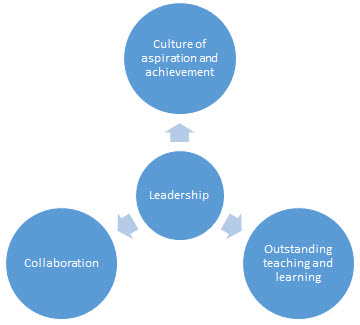

Start at the top - you don’t have an outstanding school unless you have great leadership. Seems odd to need to say that leadership is the key driver for school improvement - of course it is. But that’s just the start - great school leaders focus on three key things:

-

Outstanding teaching and learning

Again it’s obvious; of course you need outstanding teachers. I once heard a very successful executive head (running three outstanding primary schools) talk about the improvements the schools had made and how they sustained their success. One thing stuck – she said that they were very rigorous in their interview process for all staff and they don’t take people unless they were confident that they were or could become outstanding teachers or teaching assistants. They were creative with the curriculum and timetables to make it work. Being creative with the curriculum is the other key element of outstanding teaching and learning. The freedoms provided to schools to be flexible and creative with their curriculum is a key feature of the way the education system is evolving to become school-led.

-

Culture

It’s a word used regularly, but often without meaning. Outstanding schools have a culture of aspiration and achievement, amongst learners, teachers, leaders, parents and governors. I have seen this a lot in London, where schools in areas of high social deprivation don’t accept that pupils cannot achieve. It is easy to say but hard to do. An example that sticks in my mind is a head I worked with who had taken a school from the bottom one per cent of the league tables to the top one per cent and from RI to outstanding. On the first morning she asked a supply teacher who had been at the school for two years to leave due to an appalling attitude towards the children and their abilities. The school had had seven heads in three years and finally found one with the courage to make immediate change. The first step in changing an appalling culture and the start of a new journey for the school.

-

Collaboration

Collaboration is undoubtedly a key part of school improvement in the 21st century. The school-led system is driving collaboration through multi-academy trusts and teaching school alliances, but there are hosts of other partnerships through which schools benefit, such as universities, colleges and the private sector. The Outstanding Leaders Partnership in the north west is a great example of collaboration at its best, with around 30 teaching school alliances working together to provide leadership development across a region.

If the genie in the lamp could grant me three wishes, they’d be:

-

Investment in people at all levels – leaders, teachers and support staff

This would mean an end to using public money on big political showpieces and diverting all the money to schools.

-

Stability

We are moving towards an academised system, so let’s make this the last big change and then build on that.

-

An end to negative rhetoric

Let’s stop talking about our education system like it is failing. It isn’t. Yes, it needs to be improved, but let’s make the teaching profession a positive place to work. That will make it easier to attract the great teachers we need.

The process of school improvement is never simple, but there is a proven formula. All we need now is for the debate about school type and structure - a debate that has complicated and obscured matters - to fade into the background. Then the campaign to make every school successful can hinge on translating this formula into success for every school. That will still be a complicated task, of course, but it will be a simpler challenge than it is at present.

Phil Haslett is Best Practice Network’s business development director. To find out more about Best Practice Network’s online diagnostic toolkit, part of a new trust improvement model, see www.schoolandtrust.co.uk

Tags

- BPN News

- In the Media

- NPQ

- Scholarship

- Leadership

- Apprenticeship

- EPAO

- SEN

- Early Years

- School Business Management

- SBP Apprenticeship

- Early Career Teachers

- International NPQ

- iSENCo

- International Schools

- Partnership

- Teaching Assistants

- Partner News

- Events

- Job Opportunities

- Clerking

- Case Study

- PRU

- Podcast

- Level 3 Early Years Educator (EYE) Apprenticeship

- ECF

- ITT

- BPN Boost

Latest News

Introducing the Neurodiversity Network

We’ve launched a new Neurodiversity Network to support neurodivergent student teachers throughout their training. Jessica Sutton shares why it was created and how it’s already making a difference.